Trip Logs

Antarctica, South Georgia & the Falkland Islands Trip Log: December 19–January 3, 2020

December 19, 2019 | Ushuaia, Argentina

We converged on the small city of Ushuaia, all of us arriving from distant reaches of the planet for the same reason: to embark on an expedition to experience the wildlife and landscapes of Antarctica, South Georgia and the Falkland Islands. As our respective flights approached Ushuaia, the majestic clouds parted at times to provide us with striking views of the southern Andes. The glaciers, lakes and towering peaks had to be seen to be believed, and the impressive scenery seemed to go on forever.

Ushuaia was a growing outpost brimming with restaurants and shops catering to adventurers, and the launching point for our luxury Antarctica cruise. Enjoying the unique distinction as the southernmost town in the world, Ushuaia is locally known as El Fin del Mundo — “The End of the World.” We could hardly imagine a more picturesque setting from which to embark on our journey.

We gathered at Arakur Ushuaia Resort & Spa, perched high above the town with sweeping views of the Beagle Channel below. At the atmospheric property, we relaxed over a delicious lunch, and some of us hiked through the southern beech forest cloaking the lower mountain slopes.

The sky was a mix of sun and clouds, and a brisk wind brushed past our cheeks as we arrived at the pier, which was lined with fishing boats and expedition vessels. Making our way up the gangway, our group was welcomed by the A&K Expedition Team and crew of our lovely ship, ‘Le Lyrial.’ We settled into our staterooms and familiarized ourselves with the layout before enjoying some snacks and refreshing Champagne in the Grand Salon.

Following a lifeboat drill, we made our way to the theater for an official introduction to the ship and crew, joining Cruise Director Paul Carter and Expedition Director Suzana Machado D’Oliveira. Each member of the A&K Expedition Team shared some of their background, and it became clear that their passion for Antarctica and desire to share everything they had learned would make our journey truly special.

After we were treated to a fantastic dinner, we enjoyed some time on the deck and watched as Ushuaia vanished into the distance. Darkness fell over mountains, which hemmed the Beagle Channel on both sides, and small bands of South American terns and blue-eyed shags fished in the waters.

We took our last breath of South America, smelling the fresh green vegetation carpeting the mountainsides and contemplating the experiences that lay ahead. As we drifted off to sleep in our new home away from home, we eagerly awaited the vast Southern Ocean that would bid us welcome in the morning.

December 20, 2019 | At Sea: En Route to Antarctica

We awoke to the ocean rolling in every direction, with South America now well behind us to the north. The wind and swell known to define this part of the world were nowhere to be found, so we took full advantage of their absence by heading out on deck with our coffee and binoculars. As many as three wandering albatrosses were following us in our wake, and they were a spectacular sight — their 11-foot wingspan makes them one of the largest flying birds in the world.

After breakfast, we had the opportunity to exchange our parkas for more form-fitting replacements. Then, we joined ornithology lecturer Patricia Silva for her presentation entitled “Seabirds of the Southern Ocean.” She highlighted some of the species we would see in the open ocean and told stories of their amazing long-distance travel capabilities; some species regularly circumnavigate the entire globe between nesting sessions.

We made our way to the deck to watch a constant stream of blue petrels cruise past the ship. Next, we joined photo coach Richard Harker for “The Secret to Better Antarctica Photos.” A superb lecture well suited to novices and professional photographers alike, it covered everything from how best to cope with Antarctica’s challenging light conditions to protecting our camera equipment in unpredictable weather. It motivated us to get out there and capture that perfect shot.

Meanwhile, the Young Explorers embarked on a scavenger hunt to familiarize themselves with the ship. They later participated in a wildlife-watching class followed by some time on deck to scan for birds and whales.

Following Richard’s lecture, we had lunch and relaxed in one of the lounges. Later, marine mammal lecturer Matt Messina gathered us back in the theater for “Whales of the Southern Ocean and Antarctica.” From the far-reaching, low-frequency vocalizations of blue whales to the cooperative bubble-net feeding of humpback whales, he shared some riveting stories about this diverse group of mammals. We left the lecture hall excited for our first encounter with the whales of the Southern Ocean.

A few fin whales were spotted during deck time, along with a minke whale that was racing up ahead, blowing white spray everywhere. Afterward, we joined geology lecturer Dr. Jason F. Hicks for “Antarctic Ice: From Icecap to Growler.” He provided a fascinating point of view: Glaciers are actually rivers of ice, flowing (however slowly) down the path of least resistance. We learned that Antarctica’s massive ice fields can get up to two miles wide, towering above sea level by as much as 12,000 feet.

Donning our best Sunday attire, we prepared for the Captain’s Welcome Aboard Cocktail Party. The ship swayed back and forth as we mingled over Champagne, and we had the pleasure of meeting Captain Christophe Colaris, who introduced several core members of his crew. Like our fellow guests, the crew hailed from different parts of the world, gracing our vessel with international flair. Everyone had a wonderful time, and the evening was rounded off with a sublime dinner.

December 21, 2019 | Melchior Islands, Antarctica

During the early-morning hours, we felt movement from the ship as we lay tucked in our beds. The wind and swell had grown more powerful throughout the day. We took our morning coffee outside to feel the cold air on our skin, which was a clear indication that we had crossed the Antarctic Convergence last night — meaning we had passed over the continent’s ecological boundary. A lively group of Cape petrels frolicked in the air currents around the ship, their splotchy black-and-white pattern giving themselves away even as heavy snow began to fall.

We relaxed over breakfast and then joined Matt in the theater for his talk entitled “Leopards of the Deep: Ice Seals of Antarctica.” He introduced us to the unique group of seal species that live around the White Continent, some of which are found nowhere else on Earth.

Captain Colaris led the Young Explorers on a tour of the bridge to teach them about the radar used to detect icebergs ahead, along with the stabilizers that keep ‘Le Lyrial’ from rocking in rough tide.

We enjoyed some more fresh air outside as we scanned for wildlife. Later, we gathered back in the theater for a mandatory briefing concerning proper conduct ashore, led by Suzana and Expedition Leader Marco Favero. The goal was to ensure that the environment and wildlife were not disturbed by our presence. We also learned the ins and outs of the Zodiacs, sturdy inflatable boats that would be our transport of choice out here in the great white expanse.

After everyone cleaned the accoutrements we would bring ashore in order to meet Antarctica’s biosecurity guidelines, we met Richard for “Yes! You Can Capture Antarctica with Your Smartphone!” He went over some of the common photography situations we would likely encounter and offered ideas on how to best use our smartphones to capture these moments.

Later on, we met Patricia for “Birds in Tuxedos.” She highlighted some of the penguin species we would encounter on our journey, including the Adélies, which march many miles over the sea ice in October to reach their breeding colonies. It was an entertaining presentation, and we left eager for tomorrow’s arrival at our first Antarctic penguin colony.

During the early evening, ‘Le Lyrial’ entered the shelter of the Antarctic Peninsula’s islands, and the large swells we had felt throughout most of the day began to wane. We had our first views of the magnificent icecaps covering these low islands, along with a few humpback whales fluking in the windswept sea. It was here that Paul announced the winner of the spot-the-first-iceberg competition.

As we sipped our fancy drinks, we gathered for our first evening recap and briefing. Naturalist and Zodiac driver Rich Pagen introduced us to the Beaufort scale — a device used for measuring wind speeds — and Matt spoke about ocean currents in the Antarctic. After dinner, we gathered in the Observation Lounge to take in the spectacular scenery.

December 22, 2019 | Neko Harbour & Paradise Bay

We awoke to the Gerlache Strait at its finest, with towering mountains on our port side, all of them covered in glaciers that looked like frosting on a cake. The cool morning air helped wake everyone up, and soon, we found ourselves pushing through ice in our Zodiacs and zipping around stunning Andvord Bay.

We landed at Neko Harbour, named for Christian Salvesen’s floating whaling factory ship ‘Neko,’ which operated in the South Shetland Islands and the Antarctic Peninsula between 1911 and 1924. Many of us chose to hike to the ridgeline above. We ascended a steep, snow-covered hill and made our way to an outcrop from which our group could see Andvord Bay in its entirety — and what a sight to behold.

Below, we sat and watched the penguins move about their day. A glacier with cerulean crevasses cascaded down to the sea adjacent to the boulder-strewn beach. Gentoo penguins loafed along the shoreline, as did a Weddell seal, both serving as perfect subjects for our camera.

Steep penguin highways stretched from the shoreline to the nesting colonies, and we wondered what it must be like for the first penguin that arrives there each spring — a penguin who would need to break a trail for those who would follow. The gentoos were occupied with the incubation phase, and we watched patiently as they stood to reveal their carefully guarded eggs.

Over lunch, the ship passed through the scenic Aguirre Passage en route to Paradise Bay. The scenery was exquisite, and we spent ample time on deck taking in the moment and scanning for wildlife. Soon, we went ashore at Brown Station, an Argentine outpost that operates during the summer months. Gentoos welcomed us as we walked between the orange buildings, and we made our way up a steep snow slope for a magnificent view over the bay. Some of us slid down the hill, while others lingered by the station to observe curious snowy sheathbills.

Later on, we took an exciting Zodiac tour. Along the way, we saw nesting blue-eyed shags with nearly full-grown chicks, which begged for food from their parents with heartfelt enthusiasm. The vegetation on the cliffs hosted tufts of unusual Antarctic hair grass, one of only two flowering plants in the polar region. We also saw Antarctic terns and Cape petrels nesting on the ledges.

Back on board, our group gathered for recap. Naturalist and Zodiac driver John Wright discussed historic Antarctic place names, and Patricia talked about penguins and their stone-collecting habits. After dinner, we lined the outer deck railings and watched humpback whales up close. As many as a dozen were in the area, and everyone cheered each time one raised its tail fluke in preparation for a deeper dive.

December 23, 2019 | Cierva Cove & Mikkelsen Harbor

This morning, we woke up early to enjoy the stunning scenery along the spine of the Antarctic Peninsula. We ate a hearty breakfast with one eye out the window before boarding the Zodiacs for a tour of Cierva Cove, named for Spanish aeronautical engineer Juan de la Cierva, who designed the first successful rotating wing aircraft in 1923. It was a particularly scenic spot, choked with ice and flanked by impressive mountain peaks.

Base Primavera, an Argentine Antarctic base, was nestled on a hill overlooking the cove, its orange buildings in stark contrast to the frosty white and blue landscape. We cruised along the shoreline of a rocky island, where Antarctic hair grass covered the ledges and chinstraps leaped in and out of the water.

The morning’s star attraction was the humpback whales enjoying the cove as much as we were. Almost everywhere we looked, we could see these beautiful creatures surfacing and feeding in the green, plankton-rich waters. We even witnessed cooperative bubble-net feeding taking place, in which these whales forced large numbers of krill into a tight ball shape for an easy capture.

Clusters of gentoos rested on icebergs, and a lone crabeater seal frittered the day away on a small ice floe. The floe was bobbing up and down so much that we wondered how the creature managed any sleep at all.

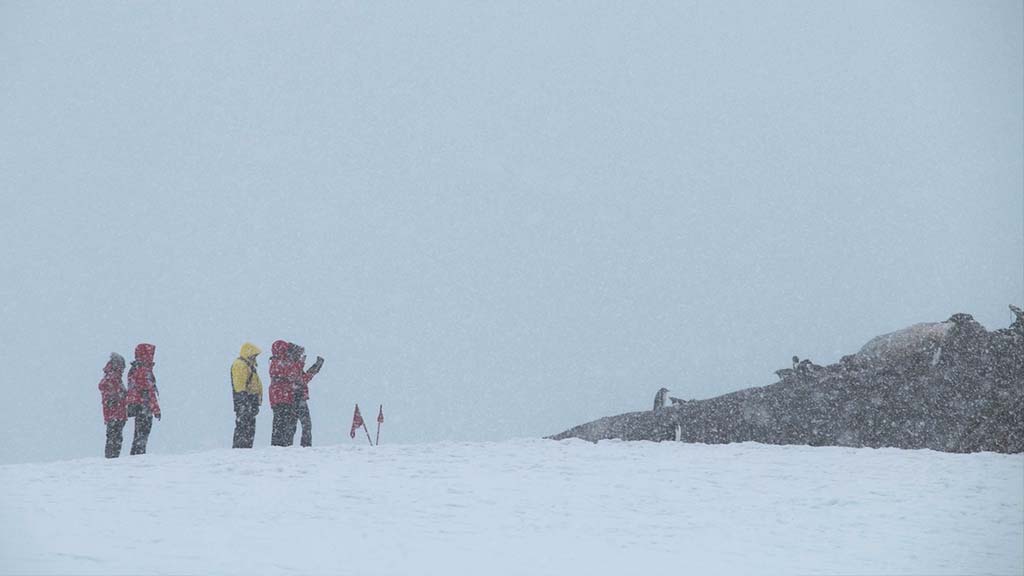

Afterward, we headed back to the ship for lunch, then sat with a journal for a while to record some of the many highlights we had experienced on our journey thus far. ‘Le Lyrial’ anchored off Mikkelsen Harbor, and we made our way to the Zodiacs for the short ride to the landing. This small bay rests on the southern side of Trinity Island in the Palmer Archipelago and was used from 1910 to 1917 as an anchorage, where whaling ships would flense their catch and boil the blubber for oil. The early-season snow had dusted most of the island, and any outcrops were occupied by playful gentoos.

Snow fell steadily as we made our way over the saddles to the backside of the island, where an orange rescue hut was nearly surrounded by gentoos. Sleeping seemed to be the activity of choice, a bold move considering the parents were on guard duty. Still, apart from defending the nesting grounds, their only real task was to keep the eggs warm. A few Adélies came ashore and sat among the gentoos, some of them putting on quite a show as they tobogganed across the snow on their bellies.

An occasional Weddell seal cruised the shallows, rising just enough for us to see its characteristic spotted gray fur. These seal types are true ice seals, heading south in the winter to feed under the fast-moving ice using breathing holes they keep open with their teeth. Mikkelsen Harbor was the perfect place to spend some time soaking up the gorgeous scenery.

Back on board, we gathered for recap. Naturalist Helen Ahern talked about photo identification of marine mammals, and Jason discussed the volcanic history of tomorrow’s landing at Penguin Island in the South Shetlands.

December 24, 2019 | Penguin Island & Turret Point

During the early-morning hours, ‘Le Lyrial’ anchored off Penguin Island. Rising from the sea off the southern coast of King George Island, this volcanic cone was discovered by Irish sailor Edward Bransfield in 1820, who served as an officer in the British Royal Navy. Chinstrap penguins were everywhere, and the whole scene was enhanced by last night’s brilliant snowfall, which blanketed the entire island from top to bottom.

We swung our legs off the Zodiac and carefully made our way to the top of a boulder beach. As we navigated above the high-tide line, southern giant petrels soared overhead, coming and going from their colony on a rocky rise above the beach. Old whale bones scattered among the large cobbles served as chilling reminders of the grisly whale harvest that took place in this area near the onset of the prior century.

At last, we reached the chinstrap penguin colony, where guano covered everything, including the chicks. Having hatched in early December, the chicks were now around three weeks old. The guano had not strayed much since they hatched, so it had begun to pile up. It was a sloppy affair, and the chicks were surely looking forward to their first swim in a month and a half, which would give them an opportunity to wash off the stink.

Some of us hiked up the flats to the rim of the main volcanic cone, which was last active about three years ago. Others made their way to Deacon Peak, the highest point on the rim at an elevation of roughly five hundred feet. A mix of sun and scattered clouds created shadows that danced across the gleaming white crater.

After lunch, we went ashore at nearby Turret Point, near the eastern end of King George Island. Above the beach berm was a large flat area popular among southern elephant seals, particularly those coming ashore for their annual molt.

Adélies came and went from their colony atop a bluff behind the beach, unconcerned with their human spectators. We wandered between rock stacks adorned with colorful lichens, moss and even Antarctic hair grass.

We returned to the ship, the Christmas spirit in the air as we dressed in festive clothing to celebrate the evening. Before dinner, we sang Christmas carols around the piano with the A&K Expedition Team — a highlight of the night. Their honey-sweet voices were so enchanting that they sounded like angels.

Later that evening, ‘Le Lyrial’ passed along the coast of Elephant Island, where British explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton and his loyal crew took refuge after they became marooned in the Weddell Sea in 1916.

Our Christmas Eve was truly magical, spent among new friends, delicious food and flowing glasses.

December 25, 2019 | At Sea

The light swell last night rocked us to sleep, and we awoke ready for a relaxing and educational day at sea. After a leisurely breakfast, we joined Patricia for the first enrichment lecture of the day: “Penguins #2: Evolution and Biology.” She began with a discussion of penguin evolution, pointing out that the closest living relatives of the penguins are the petrels and albatrosses. It was an entertaining talk that left us eager to spend more time with these fascinating creatures upon our arrival in South Georgia. Meanwhile, the Young Explorers learned about overwintering in Antarctica from John. They also made holiday cards for family, friends and even the ship’s crew.

Rob gathered us back in the theater for “Norwegian Who Took the Prize.” He provided a complete biography of Roald Amundsen, from his youth through his illustrious career as a polar explorer. Amundsen’s meticulous planning skills and his use of dogs heavily contributed to his success.

An announcement rang from the bridge that Santa Claus had been spotted on radar. It appeared he would be landing on the ship to wish everyone a merry Christmas. As festive music piped throughout the ship, Santa made his way to the Grand Salon, where he showered us with presents and cheer.

After lunch, the Young Explorers delivered their holiday cards and gathered to make Christmas cookies. These sweet treats took the forms of both traditional shapes and Southern Ocean inhabitants, including albatrosses and penguins.

We enjoyed a book in the Observation Bar before joining Jason in the theater for “Gondwana: Breaking Plates to Form a Continent.” Throughout his detailed overview of plate tectonics, we learned that these plates move in different directions very slowly, driven by convection currents generated from intense heat in the Earth’s core. Jason also leveraged famous hot spots as examples of these powerful forces in action, including the San Andreas Fault. He next focused on how these processes eventually caused the Gondwana supercontinent to break apart — resulting in the formation of Antarctica’s location at the bottom of the world.

Our group enjoyed some time on deck watching prions playing in the wind, and then we joined Richard for “Beyond Automatic: Mastering Your Digital Camera.” He enlightened us on ISO, white balance and shutter speed, and we learned how to incorporate these tools and techniques into our photography.

During our evening recap, Rob told the story of Shackleton’s right-hand man, Frank Wild, and Rich highlighted the dive-bombing behavior of terns and skuas. It was a full day of learning, and we also had time to fully appreciate the continent’s grand scale as we transited from Elephant Island to South Georgia.

December 26, 2019 | At Sea

We awoke this morning to slightly warmer temperatures, along with an entourage of prions swirling back and forth in the ship’s wake. As we closed in on South Georgia, black-browed and wandering albatrosses began to appear — surely the same harbingers Shackleton and his men experienced aboard ‘James Caird’ as they made their remarkable 800-mile journey across the windswept ocean.

After breakfast, we joined Rob for his presentation entitled “Shackleton’s Incredible Journey.” We learned about the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition from 1914 to 1917, Shackleton’s daring attempt to make the first land crossing of the Antarctic continent. Instead, the voyage became a riveting tale of courage in the face of overwhelming odds. Rob told the hair-raising story of how Shackleton and his men found themselves trapped at sea after their ship, ‘Endurance,’ became cemented in by pack ice.

A practical solution to the ice debacle was quickly underway. Men armed with iron bars and makeshift chisels attempted to hammer through the ice, but to no avail. Unable to free their ship from its frozen restraints, the crew rounded up the lifeboats and supplies and hauled them onto a nearby floe. They made camp there, hoping the sea current would carry them to civilization. In the grueling year that would follow, Shackleton and his men searched for land using lifeboats and ice floes as improvised rafts. After sailing 800 miles for what surely seemed like an eternity, the crew made their way to Elephant Island and were finally rescued. It was the first time they had stood on solid ground in 497 days.

Some of us spent time on deck scanning the slate-gray sea for wildlife. Next, Richard gathered us back in the theater for “The Perfect Penguin: Why Does Composition Matter.” During the presentation, he talked about some of the challenges a photographer faces when trying to capture wildlife in Antarctica’s ever-changing light conditions, and presented possible solutions.

After a delicious lunch, we reconvened for a mandatory briefing in order to comply with biosecurity measures that were in force on South Georgia. We talked about steps we would take to prevent the accidental introduction of foreign species to the island. Next, we vacuumed our gear and scrubbed our boots, and even signed a declaration that promised we would follow these steps each day to help protect South Georgia’s fragile environment.

Later, Matt spoke about ocean currents in this part of the world as well as the upwelling of nutrients that allows for such a productive ocean ecosystem to thrive here. He also explained how the annual formation and breakup of sea ice influences the salinity, water density and life cycle of krill, the Southern Ocean’s keystone species.

December 27, 2019 | Cooper Bay & Gold Harbour

The sky brightened in Cooper Bay as we relaxed over fresh morning coffee and buttery croissants. The Zodiacs were lowered into calm waters, and we set out on a tour of the bay, maneuvering in and out of kelp and fingerlike coves.

Snowy sheathbills picked through the algae-covered intertidal zone for invertebrates to feast upon, while the occasional South Georgia pipit flew over our heads to get a closer look at us. The beaches were littered with male fur seals defending their harems, as well as elephant seals piled together in musty throngs. Light-mantled albatrosses soared overhead in pairs. There was also a macaroni penguin colony forming a steep penguin highway that stretched several hundred feet down to the sea.

We sipped surprise Champagne as Antarctic terns fished in the shallows and northern giant petrels slowly paddled over to see what the “big black rubber thing” was doing in its waters. It was a lovely morning, with a blue sky contrasting perfectly against the tussock that covered the low slopes of South Georgia’s mountains.

Over lunch, we gazed out the window at the ice-covered peaks running down the spine of the island as black-browed albatrosses gleamed white in the sunlight. In the early afternoon, we stepped ashore at Gold Harbour, one of the most beautiful beaches in South Georgia. Gold Harbour is said to be named for the glittering seams of iron pyrite — a brassy, yellow mineral known as fool’s gold — that are found in the cliffs. We worked our way up from the landing site, carefully maneuvering around a huge gathering of elephant seals.

The air was filled with a symphony of calls, including loud snorts and belches regularly emanating from countless young male elephant seals sparring with one another on the beach and in the shallows.

Farther down the beach was the king penguin rookery, with groups of fluffy wool-coated chicks scattered around the edge. These juveniles are sometimes referred to as “oakum boys” — named by early whalers because of the resemblance the brown plumage has to the color of oakum, a tarred cotton fiber used for caulking wooden ships. Something else we found fascinating was the fact that the parents were balancing the eggs on top of their feet.

With so much scenery to absorb, conversation this morning was minimal. We could see huge mountains everywhere, along with the tumbling Bertrab Glacier. Brown skuas soared overhead and rested along the beach, always scouting for their next meal. Meanwhile, giant petrels loafed on the sand with their bills tucked carefully under their back feathers.

We returned to the ship, where we learned about South Georgia’s geology from Jason and the island’s magnificent kelp from Helen. Afterward, we sat down for dinner and shared stories of our experiences in this wild and extraordinary part of the world.

December 28, 2019 | Grytviken & Fortuna Bay

Over breakfast, ‘Le Lyrial’ made its way into the calm waters of Cumberland Bay, with South Georgia’s highest peaks looming above in the distance. Grytviken, a place soaked in history from the age of Antarctic exploration and exploitation, could be seen just ahead, tucked away in a quiet cove with its stunning natural harbor. Evidence of the former whaling operation was everywhere.

We landed on a beach just below Grytviken Cemetery. Here lies the grave of Shackleton himself, along with those of many whalers who lost their lives in the pursuit of whale oil. “The Boss” — as the famous explorer is sometimes called — perished in Cumberland Bay aboard his ship, ‘Quest,’ in January 1922, just six years after rescuing his crew from the doomed ‘Endurance.’ While Shackleton’s body was en route to England, a telegram was received from his wife, Emily, insisting that he be laid to rest in Grytviken Cemetery. Interestingly, the ashes of Frank Wild — leader of the party from Shackleton’s shipwrecked expedition — had been interred there just a few years prior, and the two gravesites lay beside one another to this day.

Some of us hiked up a steep ridge above the cemetery to Gull Lake, a reservoir for a hydroelectric plant. Others wandered past snoring fur seals and sneezing elephant seals along the shoreline en route to the remains of the whaling station. Rusty storage tanks, dilapidated whale catcher boats and old industrial machinery lay in disarray. We also visited the Norwegian Whaler’s Church. Built in 1913, it had been used for a few marriages and baptisms, but mostly for funerals, as life at Grytviken was difficult. Also visible on the mountainside just above the church were the remains of an old ski jump, used by the whalers during their extremely limited free time.

Others headed for Grytviken Museum, which was a must-see. We worked our way through the various rooms, admiring the remarkable records and natural history displays. We also stopped by the shop to browse a myriad of attractive souvenirs, including books, clothing and ornaments. The sun was shining, so many of us basked on the benches in front of the museum, while others returned to the ship for a lecture given by a representative of the South Georgia Heritage Trust.

As we ate lunch, we admired South Georgia’s soaring peaks and impressive winds. The ship made its way to Fortuna Bay, and once the anchor had been lowered, we boarded the Zodiacs. Stepping ashore, we began a one-mile hike to a king penguin rookery far up the glacial valley.

We paused to admire elephant seals stacked atop one another in the tussock, their characteristic sneezing and snorting sounds alerting us to their presence behind the grassy cover. Farther up the glacial outwash plain, groups of king penguins lounged in the stream, partaking in their annual catastrophic molt. The surface of the stream was decorated with thousands of tiny white feathers making their way down to the sea.

Soon, we arrived at the colony, where we watched everything from adults incubating eggs to whistling chicks begging incessantly for food. Skuas patrolled the skies overhead, waiting for any opportunity to drop in and nab a young chick or even one of the eggs. Several small waterfalls poured from the towering glaciated peaks above, and fur seals were everywhere.

December 29, 2019 | Stromness & Salisbury Plain

This morning, we pulled back the curtain to reveal a blue sky, green tussock and snow-capped peaks. The forecast called for strong winds, which were beginning to materialize when we arrived by Zodiac just down the beach from the dilapidated Stromness whaling station. Unlike Grytviken, the station hadn’t been cleaned up or restored. In fact, it hadn’t changed much in almost a hundred years, having been abandoned not long after whaling ceased here in 1931.

We walked past fur seals and scattered king penguins as we headed up the braided stream and its gravel bed. Antarctic terns flew overhead en route to the sea from their nesting sites. Meanwhile, gentoos marched up the valley to their nests found in the low hills to the side of the valley. We were struck by how far these penguins were nesting from the sea. The waterfall poured from the side of the glacier-carved valley as the shadows from clouds overhead cascaded down the grassy slope.

Back on the ship, Jason pointed out a mountainside in the bay with a distinct pattern on the rock face — the very landmark that told Shackleton and his men that Stromness was nearby. We sipped coffee in the Grand Salon as the ship headed west along the north coast of South Georgia. Strong winds lashed the sea surface, tearing chunks from the gorgeous turquoise ocean. While we ate lunch, Marco searched for a suitable landing.

We arrived just off Salisbury Plain, and the A&K Expedition Team determined that the landing here was a go. Our group boarded the Zodiacs, and we carefully made our way ashore. This large glacial outwash plain is fronted by a broad black-sand beach and home to one of South Georgia’s largest king penguin colonies. Flowing north into Ample Bay, Grace Glacier is named for the wife of American ornithologist Robert Cushman Murphy, who undertook much of his research here in 1912.

Once ashore, we strolled past snoozing fur seals and molting king penguins until reaching the edge of the rookery, where nearly full-grown penguin chicks — dressed in their finest woolly brown garb — were clustered around one another awaiting the arrival of food from Mom or Dad. Sunshine and bouts of strong wind shared the stage as we soaked up the peaceful atmosphere.

After we returned to the ship, John discussed the Antarctic Treaty and Rich “interviewed” a king penguin. We relaxed in the bar after dinner and shared stories of our experiences in South Georgia, which had impressed everyone with its history, abundance of diverse wildlife and formidable weather.

December 30-31, 2019 | At Sea: En Route to the Falkland Islands

Wind from the last few days had churned up a considerable swell by the time we passed South Georgia’s western tip and headed into open water for our journey across the South Atlantic to the Falkland Islands.

We awoke to find an entourage of black-browed albatrosses ushering us into Shag Rocks, which we circumnavigated during breakfast. This cluster of six rocky pinnacles, the tallest reaching 233 feet above the sea, came into view in the misty low clouds directly ahead. Soon, the guano-covered rocks were close enough that we could see the 2,000-plus pairs of nesting blue-eyed shags that give the rocks their name.

Russ kicked off the day’s lecture program with “A Year in Antarctica,” in which he shared stories of his experiences as a base commander on Signy Island. From watching the arrival of the Adélie penguins on the same day every year to exploring the insides of glaciers by rappelling down crevasses, Russ painted a fascinating insider’s look of life at an Antarctic research station.

Next, we headed for the deck and watched white-chinned petrels careen past the ship, never flapping their wings but rather using the wind’s energy for sustained flight. Next, we joined Jason for “Future Plate Movements.” He projected what our planet will look like 250 million years from now if tectonic plates continue on their present course. If this happens, every continent would come together to form Pangea II, a new supercontinent.

Lunch was served, and after our delicious meal, we caught up on some reading in the Observation Lounge. Another exciting presentation came next with John’s “Life on Ice.” Highlighting his two years spent in Antarctica, he spoke about his experiences as a mountaineer and field guide on the continent. John had assisted with several field assignments and even overwintered here.

During deck time with the A&K Expedition Team, clusters of soft-plumaged petrels maneuvered in the brisk winds, and several humpbacks and a small pod of orcas were spotted. The air was very cold, a sure sign that we had not yet crossed the Antarctic Convergence.

Next, we joined Rob in the theater for “Unsung Heroes of Antarctica.” From Edward Wilson, who collected emperor penguin eggs in midwinter to prove a link between reptiles and birds, to Irish animal lover Tom Crean, who stumbled into Stromness alongside Shackleton all those years ago, Rob brought to life in vivid detail some of the lesser-known Antarctic explorers.

The seas calmed during the late afternoon, and the sun broke through the cloud cover. At recap, Russ talked about the Zodiacs, and Mark shared some hilarious facts regarding some of the wildlife we had encountered. Then, we watched a beautiful sunset while albatrosses glided overhead.

January 1, 2019 | Stanley, Falkland Islands

With scattered clouds peppering the blue skies overhead, ‘Le Lyrial’ sailed past low-lying rocky islets en route to the protected harbor at Stanley. After watching our approach on the outer decks and enjoying breakfast, we made our way down the gangway for a morning of exploration in the Falkland Islands. This windswept archipelago of oceanic heathland is among the few places left on earth that can truly be described as “off the beaten track.” Consisting of more than 700 small islands, the Falkland Islands provide a unique ecological niche for many breeding birds and marine mammals.

Stanley was founded in 1843, born from a need for a secure and accessible port for sailing vessels owned by the British Royal Navy. However, the chosen site for the anchorage was not universally popular, and was even described in one contemporary reference as “the most miserable boghole” on the island. Nevertheless, Stanley boomed as a port of repair for ships attempting to round Cape Horn during the California Gold Rush of the 1850s. With steam-powered engines propelling the sailing industry into new territory and the Panama Canal reducing sea traffic around Cape Horn, a brief period of commercial whaling saw a demand for woolen textiles. Today, the Falkland Islands’ economy benefits from fisheries and tourism.

There were a multitude of organized tours for us to choose from. Many of us left to see the rockhopper penguins, one of the Falklands’ quintessential birds — and one we had not yet encountered on our voyage. We watched in awe as the penguins went about their business on a bluff overlooking the sea. After taking a break from the cold with a cup of hot tea inside, we hopped back in the land rovers for the trek across the muddy peatlands.

Others set out on the Long Island Farm tour, where we learned about the use of peat as an energy source. To our delight, we even had a chance to cut some ourselves. Perhaps most fascinating was how relaxed the sheep seemed to be during the shearing process, during which they would lay back in a completely docile manner. We enjoyed talking with some of the locals and gained a deeper appreciation for what life was like out in “the Camp.”

During the afternoon, some of us explored the quaint town of Stanley on foot. We took in the picturesque houses with their multicolored tin roofs, open grassy lawns often inhabited by families of upland geese, and a cornucopia of gift shops and art galleries scattered along the waterfront and throughout town. It was a lovely place to amble about, grab a foamy pint at one of the local watering holes, or relax on a bench among the fresh greenery and look out over the bay. We also visited the Historic Dockyard Museum, which shed light on the island’s history, culture and wildlife.

After a shuttle ride or leisurely stroll along the shoreline back to the pier, we reboarded the ship and made our way southeast along the coast of East Falkland en route to Ushuaia. Streams of sooty shearwaters banked in the strong winds, and occasional gentoo and Magellanic penguins were spotted in the water.

In the evening, we convened in the theater for the Captain’s Farewell Cocktail Party. We socialized over Champagne and were introduced to many members of the crew. It was an opportunity to meet all the amazing people who contributed so much to our incredible voyage. Captain Colaris came to the stage to welcome everyone to the party. He also thanked our group for sailing alongside him, and provided a summary of the highlights.

A lovely dinner was served. Then, we enjoyed a cocktail with the new friends we had made and shared stories of our experiences together. Laughter and soothing background music could be heard throughout the night.

January 2–3, 2019 | At Sea: En Route to Ushuaia

A thick fog enshrouded ‘Le Lyrial’ as we headed west toward the South American continent. We had felt some movement during the night as the ship rounded the southern tip of the Falkland Islands. By the time we had woken, the seas had settled, and we were confident today would be a relaxing and educational day at sea.

We had breakfast, and then Rob gathered us in the theater for his final talk of the voyage, “Psychology of Survivors: Charcot and Mawson.” We learned about Jean-Baptiste Charcot, who led the 1904–1907 French Antarctic Expedition aboard the ship ‘Français’ and explored and mapped much of the west side of the Antarctic Peninsula. Rob also recounted the survival story of Australian geologist and Antarctic explorer Sir Douglas Mawson, whose 125-mile solo trek back to base camp — during which he faced starvation, blizzards and perilous crevasses — was nothing short of remarkable. Everyone felt a deep appreciation for these incredible explorers, and these stories still resonate with us as a species a century later.

Paul gave a disembarkation briefing, in which we received our travel information for the journey home. He also presented a DVD film of our journey, produced by the ship’s photo crew. Many got a head start on packing, while others put it off a bit longer in exchange for a nap or time on deck to enjoy the cool breeze of the Southern Ocean.

Jason presented the final lecture of the day. In “Climate Change: Ancient Record, Modern Reality,” he took us through the research and models predicting temperature change and sea level rise globally and explained some of the consequences. He also talked about the various steps taken regarding energy production and how these small steps can make a huge difference for our planet.

‘Le Lyrial’ cruised along the north coast of Isla de los Estados, a long island with a mountainous spine of bare rock. Southern giant petrels ushered us forward as we passed small islands with large colonies of blue-eyed shags, Magellanic penguins and even groups of South American sea lions.

In the late afternoon, we watched a captivating slide show comprising photos of our experiences, compiled by naturalist and Zodiac driver Richard “Blackjack” Escanilla. The slide show featured photos of our landings, and many recognized themselves disguised behind dark sunglasses and bright-red parkas. The photos were awe-inspiring, and our experiences in Antarctica, South Georgia and the Falkland Islands were so profound they already felt like distant memories.

‘Le Lyrial’ entered the sheltered Beagle Channel overnight, named after the ship that carried Darwin — a recent college graduate of Christ’s College at the time — around the world on a voyage of discovery from 1831 to 1836. As we docked at the pier in Ushuaia, it was almost shocking to see civilization for the first time in more than a week. We had been away in an icy wilderness for so long that our senses felt heightened — the town seemed more spirited, the smell of the greenery sweeter and more robust.

We had reached the end of our extraordinary journey. The final days of the expedition were dominated by reflection and celebration. Antarctica is a place truly beyond description, a remote gem uniquely powerful and fragile in the same breathtaking moment. With all that we had been through, our group would return home with a deeper appreciation for the continent, a place worthy of protecting for generations and generations to come.

The Americas

The Americas

Europe, Middle East and Africa

Europe, Middle East and Africa Australia, NZ and Asia

Australia, NZ and Asia